NOT A Dating Sim: Disney’s Twisted Wonderland and the Connotations of Otome Games

Disney’s Twisted Wonderland, or TWST, released March 18, 2020, in Japan, and Jan. 20, 2022, in North America, is a mobile, visual novel-style gacha game – with rhythm game and RPG battle elements – that features a cast of pretty anime boys based off of (or “twisted” from) classic Disney villains in a magic academy called Night Raven College. From that description alone, you may think, “Oh, so it’s a dating sim.” If you did, you would be wrong, and so would many people who first laid eyes on the game and its promotional material. The truth is, the game centers around platonic relationships between characters and the main character, their past traumas, and their development as the game’s extensive and engaging story progresses. It’s accessible (being a free mobile game), based on popular existing Disney properties, and breaks the mold compared to other games of the same genre, so why isn’t it as popular as other gacha games?

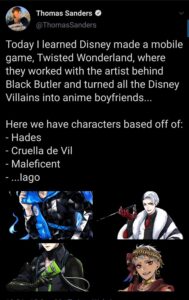

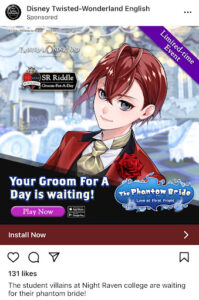

According to download stats, the game reached over 1.5 million downloads when it was launched in Japan and reached its goal of 50,000 pre-registers when localized to North America. One reason the game doesn’t have more of an audience in the West is the rampant misinformation in the game’s marketing. Whether by TWST English’s own marketing team or X/Twitter influencers responding to the game’s announcement, it was touted as a “dating sim” or an “otome” game. Otome games have their own niche audience and can be considered successful on a smaller scale, but the reason that games grouped into this genre don’t receive the wide audience they’re aiming for is because their primary audience is women. The gaming scene in general is geared toward the “male gaze,” whereas games catered to women are pushed aside, sometimes not even considered “real games.”

An otome game (meaning “maiden game”in Japanese) is a story-based game marketed toward women where the end goal is to find a romantic match. As a female TWST fan, I won’t deny that the game has women and teen girls as the primary demographic in mind. The character designs, for the most part, can be considered feminine and don’t fit the mold for Western male characters. This style is common in Japanese anime games, but that’s not why TWST has been dismissed by gamers. Other anime games with similar character designs are released in the West and become wildly successful all the time: Final Fantasy, Pokemon, Dragon Quest, Xenoblade Chronicles, Kingdom Hearts, to name a few. The answer lies in the fact that it was marketed to women.

The common theme of the games listed above is that their target demographics are boys and men. This is reflected in their gameplay: A character or group of characters, predominantly male, gather weapons, learn fighting styles, acquire allies, and progressively get strong enough to defeat the big bad. Kingdom Hearts, which also features Disney properties and has a large female audience, is no exception. The core gameplay, character writing, and presentation show that capturing such a large female audience may not have been intended. Not that this style of game is bad, far from it, but often they are very obviously meant for boys. Almost everything, from the designs of both masculine and feminine characters to the more violent gameplay, is created to satisfy the male gaze.

In anime games in particular, the male characters do sometimes look more feminine by Western standards, with big eyes, long lashes, and soft features. But once you look at the female characters, the male ones might as well be GI Joe. The male characters are made for the male players to relate to, and the female characters are for them to appreciate. No matter how the characters happen to be written, their appearances tell the audience just who they were created for.

The above images are of two dynamic and well-written characters in their respective games. Both are written to be either “protective, tomboyish, stubborn” or “confident, reckless, independent,” but you probably wouldn’t think that when first looking at them. The disparity between female characters’ designs and personalities is clear not only in RPGs but also in gacha games marketed toward men. Gacha games – ones that encourage purchases of in-game currency to buy tools used for better/easier game progression – catered to the male gaze are home to the most obvious examples of this disparity. Whether the female character is a demon lord, a dragon warrior, or a sorceress, she will have a voluptuous figure and be dressed in the skimpiest outfit and “armor” imaginable, often for no reason other than to attract male players.

It’s not that otome games don’t do similar things in terms of fanservice, but for the most part, the difference is that there is a purpose to the sexiness. The whole point is for the player to be attracted to the (usually) male leads. Even then, the clothes the male characters wear, for example a form-fitting suit, are not nearly as depraved as women’s in gacha games made “for men.” Female players can enjoy gameplay and fanservice that’s actually meant for them through the eyes of a blank-slate, typically female-presenting, MC (main character).

So, where does Twisted Wonderland fall in all of this? It’s a game in a weird place, as it has the appearance and marketing of an otome game but is meant to appeal to any gender. While games meant for either men or women usually have male or female MCs for the player to experience the game through, TWST’s MC is gender-neutral. More inclusive dating sims such as Obey Me! One Master to Rule Them All! utilize this as well, which expands the potential audience to all genders.

TWST’s main cast itself – who aren’t gender-bent versions of Disney villains but are entirely new characters based off them visually and thematically – blurs the lines between masculine and feminine. Many characters engage in some form of stereotypically feminine activities such as tea parties, sewing/fashion design, or makeup, while others participate in more masculine activities like playing sports, getting into fights, or practicing weapons combat. Depending on the character, these intersect, but no matter how the characters appear or act, they are still written to be teenage boys. The fact that most of the main cast are minors prevents overt fanservice, and there’s no romance involved in the game whatsoever.

While both women and men play TWST, it only attracts a specific type of men – queer men. Although the game was made to appeal to all genders, the audience still mainly consists of young women and nonbinary people, with some queer men sprinkled in. This is because no matter what the game developers may do, it’s still a game made “for women” and will subsequently be denounced by the majority of the gaming world’s population – straight men.

You might think that some straight, male, hardcore gacha fans would give TWST a shot, but the truth is disappointing. Many male gacha players have gone on record saying that they play these games to ogle the female characters, and the games feel less appealing to them without a sexy female character on screen. It’s not necessarily that men need to change their gaming preferences, it’s just that to get any recognition as a “gamer,” it’s clear that you have to like certain types of games – ones made with men in mind. If a woman (or female-presenting person) tells a straight male gamer they like video games like Mystic Messenger, the man would probably either stare in confusion, laugh, or say something along the lines of “that doesn’t count.” It doesn’t help that many games made for the female gaze are gacha games, which many gamers denounce for their shady gambling-esque practices. Gacha game fans have essentially made their own community separate from the main gaming community, yet female fans and otome players are pushed out from there as well. For a woman to be considered a gamer and let into any gaming world, they often have to sacrifice their own gaze and preferences, while men almost never have to.

Even though games geared toward both men and women have many of the same elements, whether a game is put down or lifted up is determined by its genre, marketing, presentation, and audience. Unfortunately, it doesn’t matter if an otome game (even if it doesn’t fit the mold of one) has good writing and overall quality, the fact that it’s meant for women is enough for straight men to denounce and ignore it. The female gaze and female gamers are just as important to the vitality of any video game genre, and a game should not be considered less-than because it has more pretty guys than pretty girls.