Bounce is Essential

The year is 2009. I am the only child still alert in the car as my siblings drool and snore in the backseat of my mother’s white Ford Explorer after she picks us up from my grandma’s place in Jackson, Mississippi. The radio station 99 Jamz wouldn’t put songs into Bounce remixes until around 11 p.m. The music blasts from the radio without the interruption of a DJ around this time of night. My mom is more open with her life, telling me the secrets of her youth and how my grandma would treat her, my oldest uncle, and my youngest uncle differently, as songs are remixed over the airwaves. My mom also tells me how when my grandpa remarried, his wife was cruel to her and even made her stand outside for their wedding. While this happens, Bounce has little to no censorship. I hear the call-and-response-styled lyrics about unfaithful lovers, partying, and the names and numbers of various wards in New Orleans coupled with the fast-paced beat that makes me feel as if I had a ping-pong ball bouncing in my brain, but in a way that made me happy. I did not understand these emotions. I did not understand why my family members would get angry with me when I listened to Bounce in the daytime or why my mother would only have these conversations with me from the freedom of prying ears. I didn’t understand until the summer 2016 that Bounce music was more than provocative lyrics and fast beats. It represented freedom and autonomy.

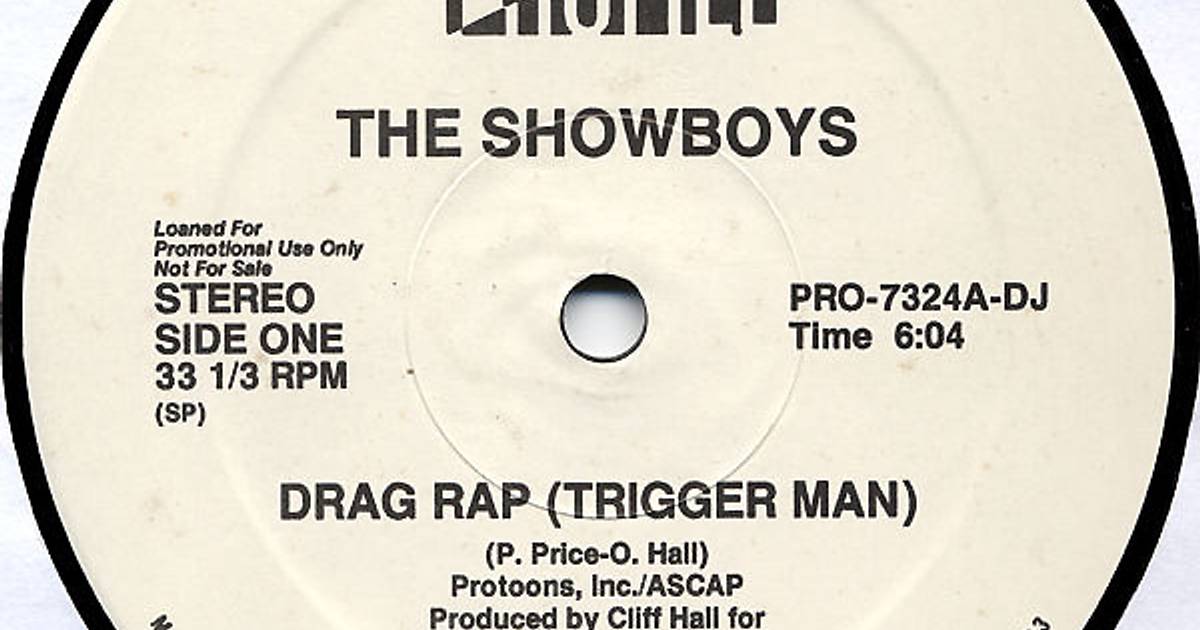

Bounce originated in the Black community in the late 1980s-1990s in the projects of New Orleans. The music is characterized by its call-and-response chants in the chorus, sexual or controversial lyrics, quick beats,

the Trigger Man beat from Trigger Man’s song “Drag Rap,” and, more importantly, shoutouts to the areas within New Orleans along with lyrics that describe the Black culture of New Orleans. Much of Bounce is second-line band-inspired. Second-line bands produce a Jazz and Blues music hybrid performed by various brass bands during funeral procession parades that felt anything but funeral-like with joyous singing and dancing akin to its protege Bounce.

Since New Orleans is only two hours and thirty- minutes from Jackson, Mississippi, and Jackson has a similar Black demographic to New Orleans, Bounce music exploded on our music stations, too. However, the similarities between New Orleans and Jackson end there because radio DJs would only play Bounce music at night or infamous clubs such as Freelons in Jackson, whereas in New Orleans, Bounce music would be prevalent from the radio, Bourbon Street, colleges, and even the cat cafes nestled in the French Quarter.

My grandmother would refer to Bounce music as a“mess” and scowl if it happened to sneak onto the radio earlier than 11 p.m.

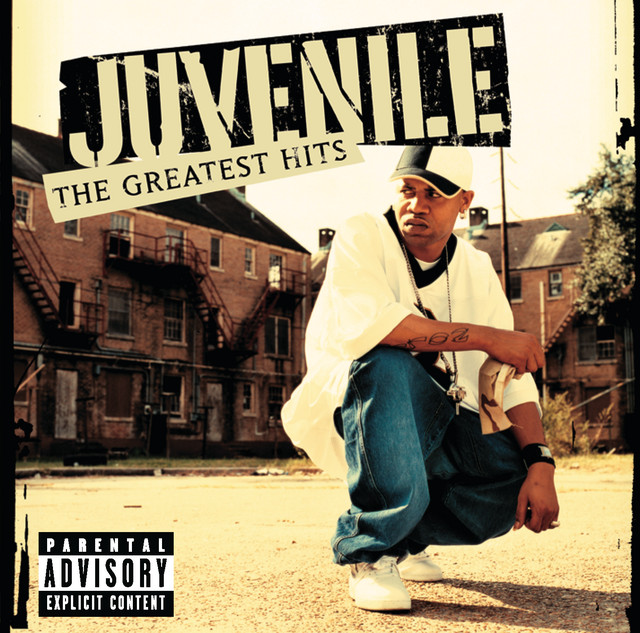

In middle school, the Bounce remix of “Back Dat Azz Up” played during our middle school dance. Our conversations about the latest childish shows ceased when the opening instrumentals began. All I remember is being shoved as about 100 hormonally charged 11-14-year-olds charged onto the dance floor to the South’s biggest Bounce song. I even got a couple of rhythmically challenged dance moves in before I heard the loud voice of my principal going, “Oh hell nah!” over Juvenile going, “You’z a fine motherfucker won’t you back that azz up.” Storming as fast as we did across the gym floor, our principal made our DJ back out of the gym, ending our school dance prematurely and only increasing my wonder about this forbidden genre.

Bounce music’s forbidden nature continued to intrigue me throughout my life. I snuck in some Bounce songs while inventorying at my high school’s library. I even listened to Bounce music to the point that it partially influenced my college application in my senior year. I listened to Bounce music as I hosted my Silent Hill-themed Dungeons and Dragons group to numb the impending doom of my friends and me leaving each other after high school. I listened to it on break from bussing tables at the Chateau to pay for my dorm supplies. In the summer of 2016, I was headed to college at Dillard University in New Orleans, the Bounce capital of the world. I listened to DJ Fresh Prince’s “New 2016 Bounce” until my cell phone died while I was minutes away from my new Bounce-infused life at the daunting gates of Dillard University.

The strange thing was I rarely moved my body to this music. I would not internalize the words or go out and do the acts in the song. I would laugh at some of the lyrics and shake my head, but I enjoyed the feeling more. Here I was, packing and preparing to go to college in the world’s party capital with music promoting good times, while my current situation was anything but good. My mom and my five siblings were sleeping on the floor of my grandma’s one-bedroom apartment after being laid off with many of her other coworkers as hospital laundry attendants. Tensions at my grandmother’s were at an all-time high, and I feared we had to walk on eggshells until my mother secured a new job. Bussing tables in Chateau for older white people, I was met with racial slurs and breadbaskets flung at me when I was not fast enough. However, I had to endure this because I had to pay for my college fees, dorm items, and a way to get to New Orleans. Those long conversations my mother and I would have as we drove late at night were replaced by tense arguments, prompting me to long for the days when I am rid of it all. I felt trapped, uncertain, and even guilty for wanting to leave Jackson.

All I had was my Bounce music and the countdown to college keeping me going. The chants and the beats constantly whirled around in my head and comforted me despite the lyrical content that others in my life so fervently stood against.

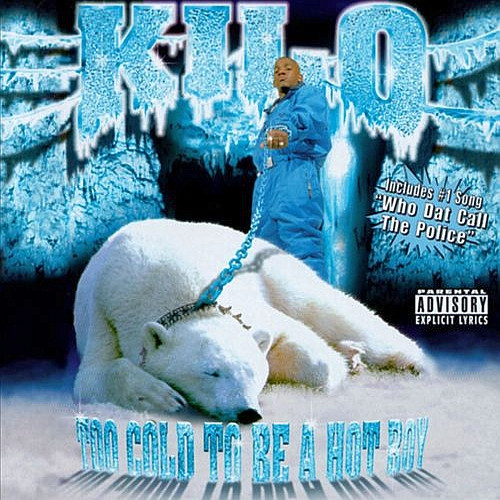

“Who called the police? Kimbrough Called the Police!!” Some had even turned on the bounce beat as we all stood outside Dillard’s Professional Schools and Sciences building almost three months after I began life as a freshman. David Duke, the infamous white supremacist, decided to utilize our campus for his campaign speech; many students did not like that. Bounce music appeared at this protest as a Red Kia pulled in front of the building and blasted the instrumental of Kilo’s “Who Dat Called the Police” as the crowd responded with words of protest. At that moment, I was terrified, constantly looking around to ensure my fellow protesters were still behaving.

I also kept an eye on the cops just in case anything went awry. However, at that moment, I felt invigorated and free. Bounce music increased the crowd’s adrenaline. Somebody had bought a small grill, and people exchanged contact information. I felt a sense of belonging and freedom, with the bouncing rhythm amplifying my mood and masking my fear until one random guy who didn’t even attend our university threw an object at Duke when he walked out of the building.

The Bounce music ceased, and anyone towards the front of the crowd was pepper-sprayed. Like the DJ from my middle school dance, I bounced right out of there with “Who Dat Call the Police,” living rent-free in my mind as I rushed back to the safety of Camphor Hall after the scariest, most exciting night of my nineteen-year-old life.

“Why do you listen to that ghetto-sounding crap?” My joy from bounce music became one of the numerous points of tension with my then-boyfriend, Liam. I’d sometimes see the look in people’s eyes at the mention of bounce music and the assumption that you were “ghetto, classless, or trashy” if you found yourself a fan like me. I could see the beauty and pride hidden within Bounce music when the artists shed light on the neighborhoods they represented. Even at an event such as a protest or memories like a nostalgic car ride, Bounce is essential to an entire culture’s spirit.