A Lukewarm Defense of The Game Awards

You ever meet somebody who doesn’t do number scores? Like, you see a movie together and you ask them to rate it out of ten and they say something like, “How could I possibly boil down my feelings into a single number?” Utterly obnoxious. Just play along, you pill. And you want to know the worst part? They’re right. I feel much the same way about awards shows. Crowning any one given project as the best in class for that year feels as arbitrary as giving Spy Kids 3-D: Game Over (2005) a number score. Both, to me, are utterly useless exercises in quantifying the unquantifiable, but nevertheless, I’m compelled by the outcome. I suppose that’s why I tune into the Game Awards, the only awards show I watch, year after year.

I reluctantly admit that I’m glad the Game Awards exist. Geoff Keighly, the show’s creator and host, comes from an earnest place in wanting to spotlight game developers, content creators, and anyone and everyone within the gaming space. One of Keighly’s objectives for the show was to demystify gaming studios and show the names and faces of the real people who labor hard to make our favorite games. What keeps me from fully hating the show is it’s important to modern gaming culture. A centralized place for gamers and industry agents alike to commiserate about their passions is a net positive for gaming as a whole, but the Game Awards is not a mythical oasis free from the industry’s toxicity—it is the industry.

The first thing many people think of when they think of the Game Awards are the trailers. Perhaps an unpopular opinion, but I’d actually consider them an advantage the show has over other awards programs. In-ceremony advertisements playing between each award might sound like a late-stage capitalist nightmare, (and it is), but I won’t pretend like it doesn’t help an audience member keep going. On average, I only play one or two new games a year, more if I’m smart with my money or not indulging in other hobbies. If a category exclusively features games I haven’t played, I can at least depend on some trailers before and after it sparking some curiosity for a future title or following up on a series I already like.

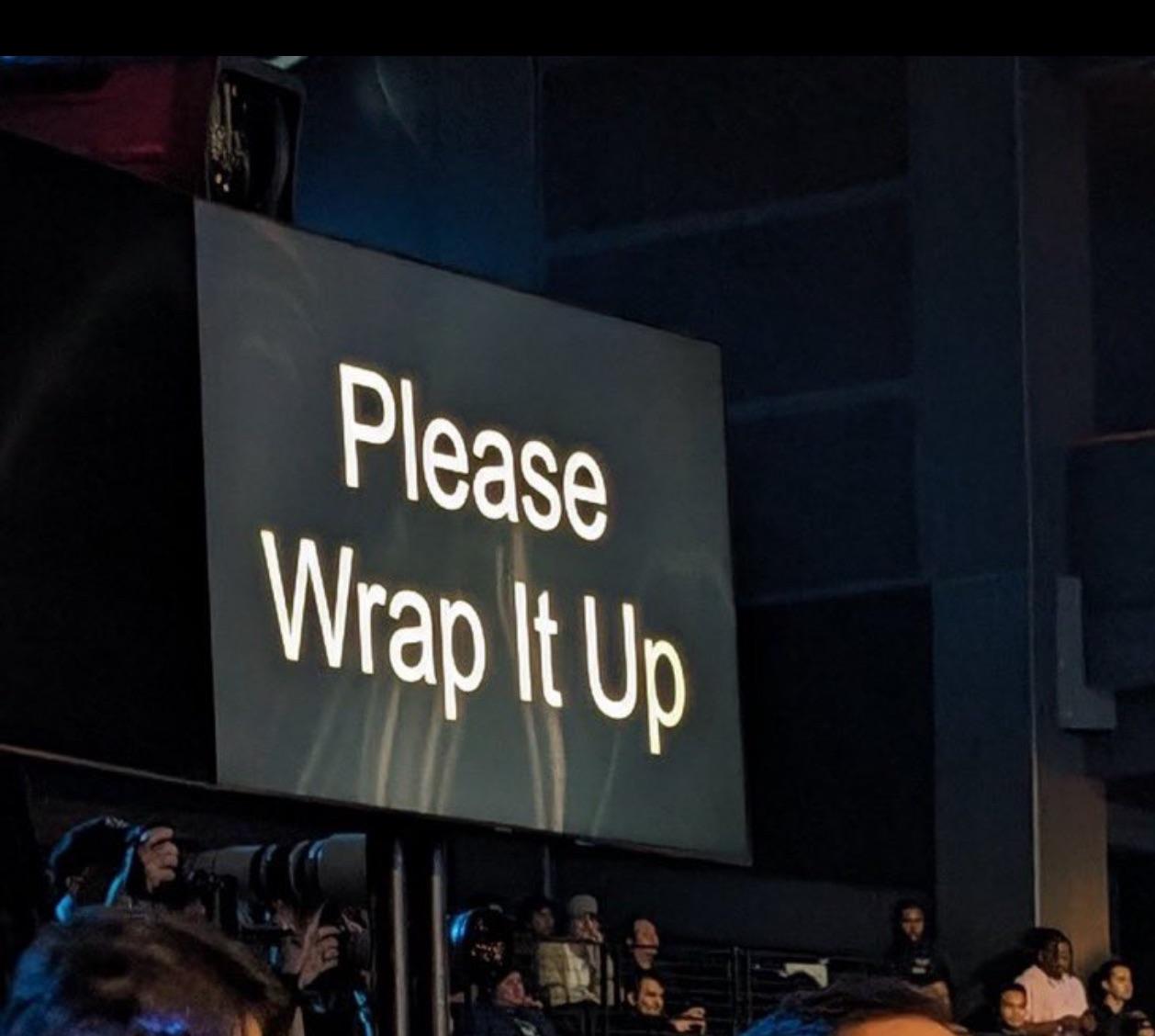

Game trailers noticeably took up a larger portion of last year’s show, drawing widespread criticism from casual viewers and community members alike. The infamous image of the teleprompter telling the Baldur’s Gate 3 devs to “wrap it up” is responsible for a major blow to the show’s reputation. Gamers, however, seem ready to forgive and Keighly seems ready to do better. Ads becoming less of a presence while giving more time to devs and presenters is the way to go. And don’t even get me started on the needless celebrity cameos. As if the video game industry couldn’t possibly be even more jealous of Hollywood, they’ll invite The Rock or Anthony Mackie to ham it up on stage.

Undeniably, however, the show has contributed many celebratory moments in gaming. Take a look at last year’s performance by the Alan Wake 2 team if you want to see how the Game Awards does in fact allow its contributors to celebrate their successes. Giving the devs this space allows them to reach their fans but also potential new fans just hearing about their title for the first time thanks to a nomination. I can say that the “Herald of Darkness” performance put Alan Wake 2 on my radar, and Balatro’s 2024 nominations got me to play it. Credit where credit is due, the Game Awards does bring increased attention to titles that deserve it.

My real problem with the Game Awards, and all awards shows, is their biases. Take the Oscars, for instance. “Oscar-bait,” a term lobbed at war epics, biopics, and slow-burn character dramas, denotes the films that the Academy tends to recognize, while genre films (horror in particular) might get nominated but hardly ever win. Unlike the Oscars, which has a big disconnect between viewers and the Academy, the Game Awards has too deeply absorbed the biases of its audience. Gamers have a narrow view of what a “good” game is. When looking at the Game of the Year nominees, two stick out: “Shadow of the Erdtree,” the expansion to 2022’s Elden Ring (we’ll get to that), and indie poker roguelite Balatro (read all about it here). All except Balatro are single player, combat-focussed, narrative experiences. Online reactions to the card game’s nomination have ranged from die-hard fans celebratorily shouting from the digital rooftops to those unfamiliar with the game dismissing it outright because of its genre. The industry’s constant pursuit of lifelike graphics and cinematic storytelling have cultivated in the gamers that this is the highest pinnacle that games as an art form can achieve. These are the games that are good. If we see “Erdtree” or Final Fantasy 7: Rebirth win GOTY, it’s the gaming equivalent of Green Book (2021) or Oppenheimer (2023) winning Best Picture.

The Game Awards is not a sanctuary free from the industry’s toxicity—it is the industry. It embodies all of the biases on the part of companies and consumers. Look no further than the nomination of “Shadow of the Erdtree.” I’ll admit that I’ve never played any of FromSoftware’s Dark Souls titles, but regardless of how good this expansion truly is, why is it nominated for GOTY? Of course, the Game Awards issued a statement explaining why an expansion to a game released last year counts for this year’s category. Their “quality first” attitude is admirable, but a slippery slope. Sure, “Erdtree” might be 60-80 hours in length, constituting a whole entire game by the standards of time and effort, and its defenders are quick to bring up these statistics, but they fail to address the core of the issue: a DLC/expansion is, categorically, not a separate title.

Why nominate “Erdtree” if not to continue the industry wide, near universal praise for FromSoftware and their titles? Mind you, the Game Awards does not have a dedicated DLC/expansion category, a simple solution that would prevent them sharing space with GOTY nominees while commemorating the quality of “Erdtree.” DLCs are deserving of awards. Hell, there are DLCs that are even better than their base games, but how does integrating them into the GOTY category effectively discuss this or even reward the work developers put into post-launch content? How does this celebrate them?

The Game Awards forgets it isn’t the only game in town. The Golden Joystick Awards, BAFTAs game awards, and D.I.C.E. awards have been doing gaming shows for much longer. Geoff Keighly making his show the show, whether you think it’s fair or not, invites greater criticism for the “biggest night in gaming.” Whatever takes home the GOTY this year, let’s not forget that there are plenty of other shows that deserve our attention.

Undeniably, Geoff has achieved his goals. His show has become the authority on year-end awards for gaming, and while I certainly have reservations about that, I do believe that his heart is in the right place. This year’s ceremony will be the true test of his capacity to listen to fan criticism and adapt his show to meet it. At the time of this writing, the Game Award’s is tomorrow night, and I am wracked with anxiety knowing this article might age like milk. Despite myself, I look forward to it, this year and years past, because it really is the biggest night in gaming. I love that developers, games journalists, and creators attending get to dress up and have a formal event dedicated to the hard work that has gone unseen for too long. For all of my criticisms of Geoff and his show, I’m glad gaming has something like this; a universally celebratory night for gaming.